As countries such as South Africa become more urbanised it has become critically important to understand how the increasingly populous areas impact physical activity. However, it can be challenging to gather an accurate, contextual understanding of the environment, which is beneficial to both researchers and residents.

Our recent publication in the Journal of Urban Health, Virtual Assessment of Physical Activity–Related Built Environment in Soweto, South Africa: What Is the Role of Contextual Familiarity? challenges the current belief that anyone, anywhere, can assess and study the built environment using virtual tools. We asked whether familiarity with the area being audited influences how we measure the built environment, particularly in relation to physical activity.

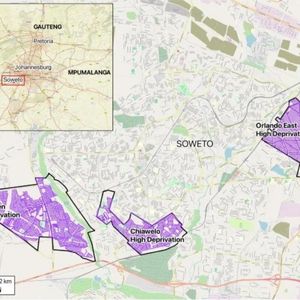

To explore this, we conducted a virtual environmental audit using Google Street View and the internationally validated Microscale Audit of Pedestrian Streetscape – Global version (MAPS-Global). Our study focused on Soweto, South Africa, one of the GDAR research sites. Data collectors were from the GDAR network, representing Australia, Cameroon, Nigeria, South Africa, and the United States. Importantly, the team included auditors both familiar with the Soweto context and those with no prior exposure to the area.

Our findings revealed that contextual familiarity plays a crucial role in the reliability of virtual audits. Researchers who lived or worked in Soweto or Johannesburg consistently demonstrated higher inter-rater reliability when assessing physical activity-related features compared to those less familiar with the environment.

The results also exposed limitations in auditing tools like MAPS-Global when applied to African urban environments. While virtual tools are efficient and resource-saving, they may struggle to capture the full complexity of rapidly urbanising cities like Soweto. Many aspects of Soweto’s streetscapes, such as informal paths and local infrastructure, were difficult to interpret for auditors unfamiliar with the area. This highlights the importance of contextual familiarity in enhancing the accuracy and applicability of research tools.

This study reinforces the need to combine global tools with local expertise. Over reliance on the idea that collecting more precise, standardised data from more places will reveal the “right” answer assumes—incorrectly—that findings can be universally applied. On the other hand, focusing solely on local nuances without a broader perspective may lead to hyperlocal solutions that miss valuable insights from transnational discussions on healthy and equitable urban development. It may also cause local decision-makers to overlook successful solutions from other regions.

In conclusion, to maximise the effectiveness of virtual tools in global health research, we recommend incorporating local expertise and adapting auditing tools to better suit local contexts.