José Izcue Gana, GDAR and MRC Epidemiology Unit PhD student, describes his recent data collection experience in Kenya. His PhD explores how the built environment influences diet and physical activity, and finding policy levers and opportunities for interventions.

I landed in Kisumu on the 20th of July. The city, located almost exactly on the equator, is known as the gateway to Lake Victoria—the largest freshwater lake in Africa and a key resource for the local economy.

I was warmly welcomed by Charles Lwanga from KEMRI (Kenya Medical Research Institute) and met the rest of the team the following day: Prof Charles Obonyo, Gladys Odhiambo, Lilian Sewe, Vincent Were, and later Grace Githiri from UN-Habitat. We spent the first few days working closely together to prepare for the two main events that had brought me to Kenya: the third stakeholder consultation session to share recent findings from the GDAR Spaces research in Kenya, and a workshop designed to explore the drivers and consequences of the country’s ongoing nutrition transition.

Community self-help and food security

The stakeholder consultation session took place on the 23rd of July. It focused on the role of (mostly) women-led community self-help groups—locally known as chamas—in preventing non-communicable diseases through the promotion of household food security in Kisumu County.

I was struck by the high level of attendance and the depth of engagement from participants. Stakeholders listened attentively and actively contributed to the discussion, sharing experiences and challenges from their communities. The session was a great success—you can read more about it here.

Understanding the Nutrition Transition

The following day, the KEMRI team and I hosted a diverse group of 14 stakeholders for a workshop focused on the nutrition transition. Participants came from a range of sectors and backgrounds: farmers, nutrition academics, policymakers from the agricultural sector, an anthropologist, representatives of youth and slum-dwelling communities, and even an 82-year-old “mama”—a respectful title for an elder woman—who still works the land and offered moving reflections from a generation that lived through the country’s independence.

The term “Nutrition Transition” refers to the shift from traditional diets—rich in minimally processed staples—to increased consumption of foods high in added sugars, unhealthy fats, and refined carbohydrates. In Kenya, this transition is accelerating due to rapid urbanisation, changing food environments, and the growing influence of globalised food systems. As a result, the country is facing a “triple burden” of malnutrition: the coexistence of undernutrition, micronutrient deficiencies, and diet-related chronic diseases such as obesity and type 2 diabetes.

A short visit to the nearest supermarket gave me a first visual impression of the transition: Ultra-processed foods from multinational corporations sitting in shelves next to fresh produce of local vegetables such as arrow roots, cassava, sweet potato, etc.

A systems approach: Group Model Building

The workshop used a Group Model Building (GMB) approach—part of the broader field of Systems Thinking, which aims to understand complex and interdependent challenges like the nutrition transition.

After Charles Lwanga led introductions, Prof Obonyo and I explained the session, outlining the objectives and how we would work together. We then facilitated three structured exercises with the support of the wider KEMRI team. The first focused on open dialogue: participants shared their insights and experiences, all acknowledging that Kenya is indeed undergoing profound dietary changes. Together, we identified over 40 variables that shape or are shaped by this transition—ranging from childhood undernutrition and adult obesity to underlying drivers such as the commercialisation of agriculture, increased marketing of processed “Western” foods, generational shifts, rural-to-urban migration, modern urban lifestyles, changes in parenting and school food environments, and an excessive national focus on economic growth (at the expense of other priorities).

One clear insight that emerged was that the nutrition transition is not unfolding uniformly across the country. Kisumu, as one of Kenya’s 47 counties, was described as markedly different even from neighbouring settlements—underscoring the importance of local context in shaping food environments and behaviours.

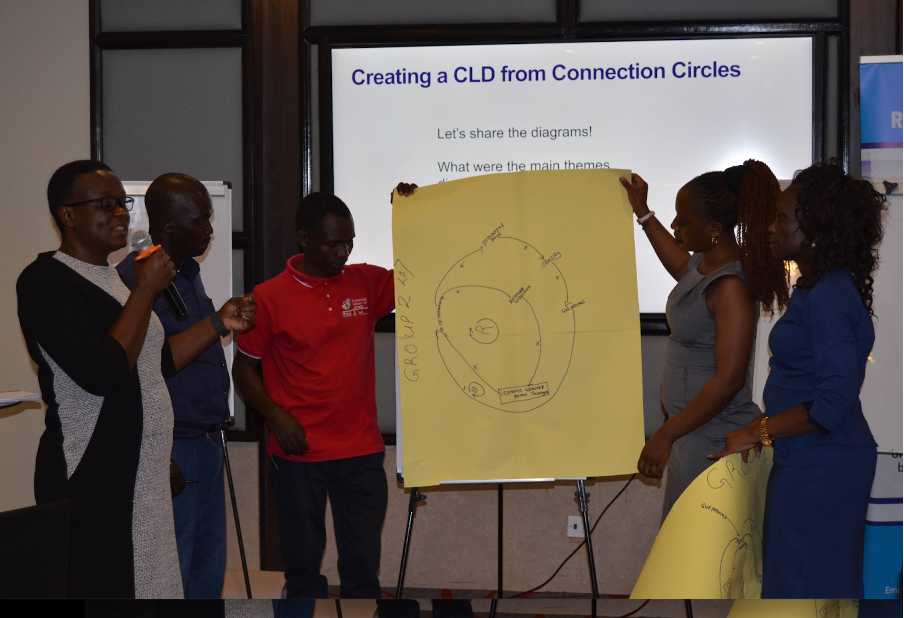

Mapping the system

In the next stage of the workshop, participants broke into small groups to map out how these variables interact. They drew preliminary causal links, explained their reasoning in plenary, and eventually translated their understanding into draft Causal Loop Diagrams (CLDs)—visual representations that depict feedback loops and system dynamics.

I was then happily surprised by KEMRI and other colleagues who celebrated Prof Obonyo’s recent 60th birthday with cake and singing. We wrapped up with a well-deserved lunch, following an intense but energising four-hour session. Despite their exhaustion, participants expressed appreciation for the opportunity to contribute and learn from one another in a structured, inclusive setting.

Final reflections and gratitude

The next day marked the end of my stay in Kisumu. To celebrate, the KEMRI team and I enjoyed lunch by the lake. I even attempted to eat ugali and tilapia fish the proper way—with my hands. I made a mess of it, much to the amusement of my colleagues, whose plates remained spotless. They laughed and told me this was a perfect reason to come back again—and stay longer next time.

I am deeply grateful to the KEMRI team for their warmth, hospitality, and collaboration throughout my visit. Special thanks to Charles Lwanga and Prof Obonyo, who went above and beyond to make me feel welcome and to ensure that everything ran smoothly.

The draft CLDs created during the workshop will now be refined, validated, and presented back to stakeholders in a follow-up teleconference. This next step will not only help us reach consensus on how the system underlying the Nutrition Transition operates, but also allow stakeholders to better understand one another’s perspectives—and ideally, to begin identifying points for future action and transformation.